Observational Data on Sugar Intake Patterns

February 2026

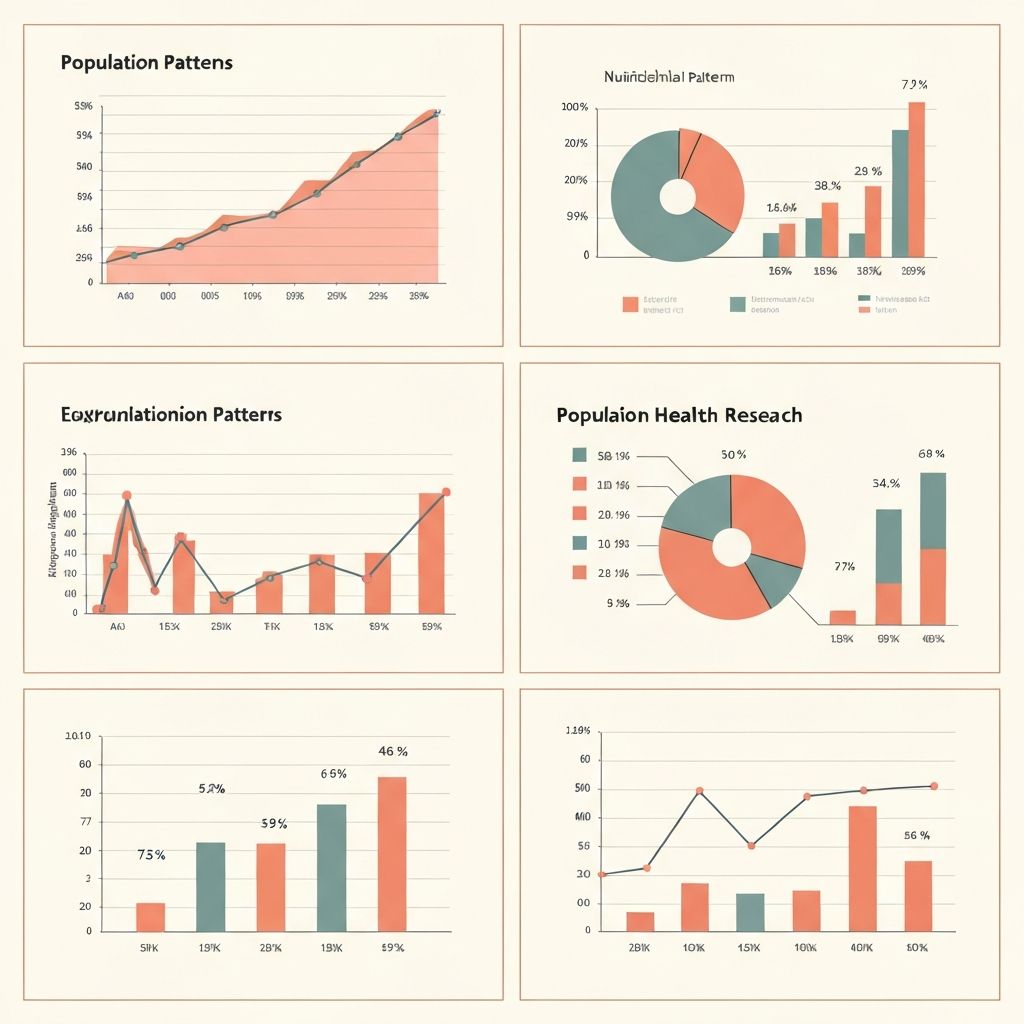

Population-Level Research Associations

Population-based nutritional research has documented associations between higher sugar intake and increased average body weight across groups. Large prospective cohort studies following thousands of individuals have found correlations between estimated dietary sugar consumption and BMI (body mass index) measurements. Cross-sectional analyses comparing populations with high versus low sugar consumption patterns show consistent associations with body weight differences.

However, these observational associations do not establish causation. Observational research examines natural patterns in populations without experimental manipulation. Individuals who consume high amounts of added sugar differ in numerous ways from those with low sugar intake. These differences include overall energy intake, physical activity levels, socioeconomic status, education level, other dietary components, sleep patterns, stress levels, and numerous genetic and behavioral factors. Any or all of these variables may contribute to the observed weight differences alongside sugar consumption.

Confounding Variables in Population Studies

A central limitation in observational nutrition research is confounding—the presence of unmeasured or inadequately controlled variables that explain observed associations. A person who consumes large quantities of sugary beverages may also consume more total energy, engage in less physical activity, have lower socioeconomic resources for nutrition, experience higher stress levels, and have sleep deprivation. Each of these factors independently associates with higher body weight. Distinguishing sugar's independent contribution from these other factors is methodologically challenging.

Statistical methods like multivariate adjustment attempt to control for known confounders. Researchers statistically adjust for total energy intake, physical activity, education, and other measured variables to isolate sugar's effect. However, unmeasured confounding remains possible. Furthermore, adjustment for total energy intake inherently assumes that sugar and other foods are functionally equivalent sources of calories, which may mask differential effects if they exist. The ability of observational research to establish causation is fundamentally limited by the complexity of real-world eating patterns and human behavior.

Temporal Relationships and Reverse Causation

Prospective cohort studies follow individuals forward in time, assessing baseline sugar consumption and later measuring weight change. This temporal sequence supports a directional relationship in which sugar intake precedes weight change. However, even prospective data can be complicated by reverse causation—the possibility that weight status influences dietary choices rather than vice versa. Individuals gaining weight might increase sugar consumption, or individuals concerned about weight might reduce sugar intake in response to early weight changes. Distinguishing the direction of these relationships from observational data is difficult.

Life events, behavioral changes, and metabolic alterations can all cause correlated changes in both sugar intake and body weight without sugar being causally responsible for weight change. For example, a period of stress or depression might simultaneously increase sugar consumption (through comfort eating) and affect weight through altered metabolism or activity. The observed association between these variables would not indicate that sugar causes the weight change, but rather that both respond to the underlying stress.

Controlled Study Evidence

When researchers conduct controlled experiments—providing diets and measuring outcomes in laboratory settings—the effects of sugar reduction become more modest. Studies in which researchers directly control food intake and reduce sugar while maintaining total energy intake show minimal weight loss. This contrasts with the associations seen in observational research, suggesting that total energy reduction (rather than sugar reduction per se) drives weight changes. When total energy is held constant and only sugar is reduced, weight loss is not observed.

Short-term controlled feeding studies (weeks to months) provide metabolic information but may not capture longer-term adaptations. Some research suggests that weight loss when sugar is reduced occurs because overall energy intake decreases—people switching from high-sugar diets to low-sugar diets spontaneously eat less total energy, likely due to reduced palatability and increased satiety from whole foods. This would support an energy balance mechanism rather than a specific sugar effect.

Individual Variation in Response

Population averages mask considerable individual variation. Some individuals show stronger associations between sugar intake and weight than others. Genetic factors, metabolic characteristics, insulin sensitivity, gut microbiota composition, and behavioral traits all vary between people. Research examining genetic variation (polymorphisms) in genes related to taste perception, appetite regulation, and nutrient metabolism demonstrates that sugar responses are not uniform across the population. Some individuals appear metabolically or behaviorally sensitive to sugar consumption, while others show minimal association with personal sugar intake and weight.

This individual variation is why population-level associations cannot reliably predict individual outcomes. A strong population-level association between sugar and weight does not mean that reducing sugar intake will produce weight loss in any particular individual. The complexity of human nutrition and metabolism means that interventions that produce average benefits across groups may have variable effects, with some individuals responding substantially, others minimally, and some not at all.

Educational Notice: This website provides general educational information only. The content is not intended as, and should not be interpreted as, personalised dietary or health advice. Relationships between dietary components and body composition are complex and vary between individuals. For personal nutrition decisions, consult qualified healthcare or nutrition professionals.